Why I'm Not Ashamed of Being a "Bad Kid"

How deviance helped me survive child abuse.

Amanda Ann Greogry

As if experiencing trauma isn’t enough, there’s the shame that comes from what one does in order to survive it.

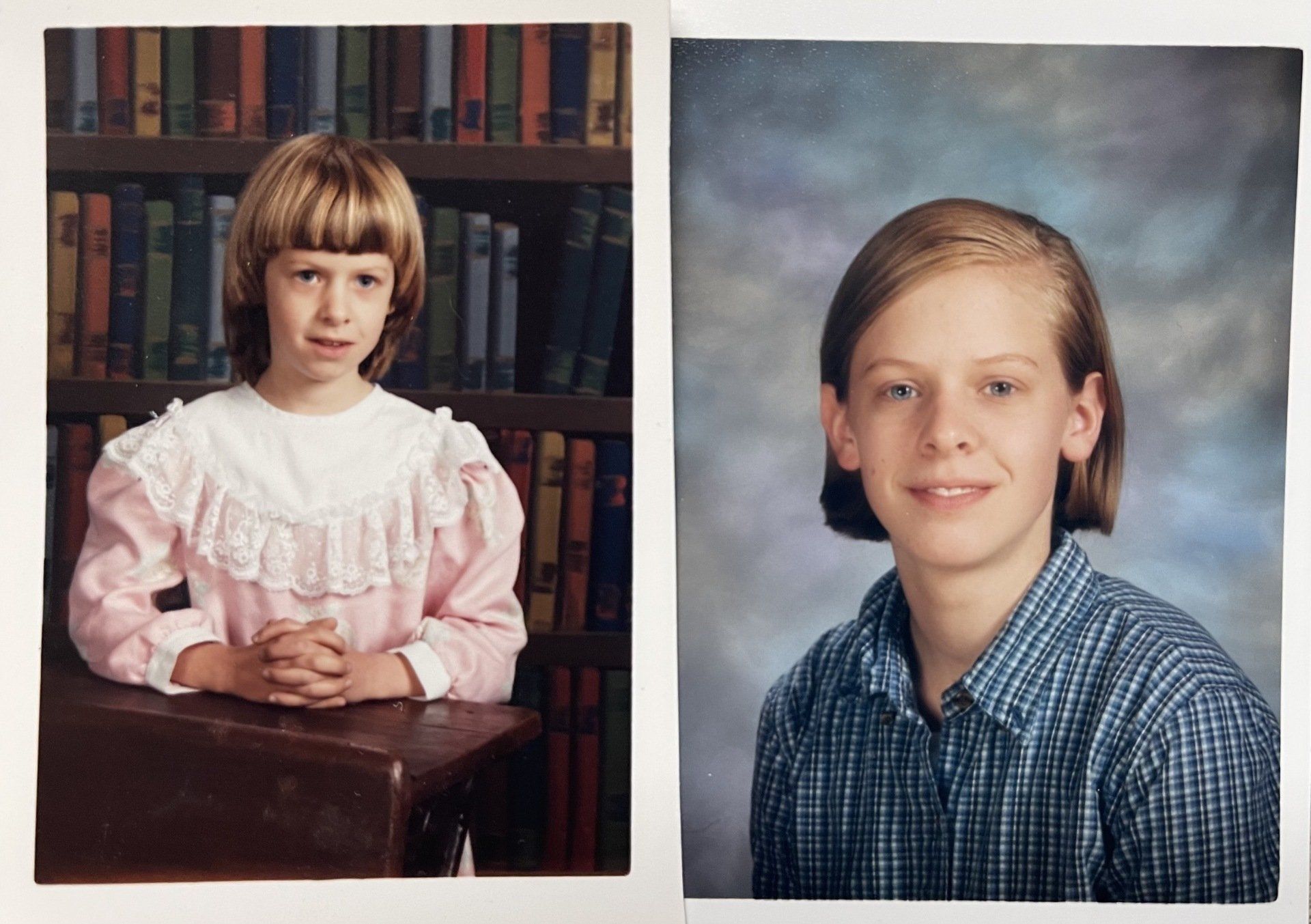

I experienced physical and emotional neglect throughout most of my childhood, and the shame that accompanied what I had to do in order to survive haunted me for years; worse yet, I encountered people who judged me for what I did – for what I know now I had to do – thus reinforcing my shame. They said things such as, “you could have made better choices,” and asked naïve questions like “why didn’t you tell someone?” These common remarks and questions may stem from good intentions, yet they are soaked in the venom of victim blaming. My shame caused me to constantly question whether I was a “bad kid,” when in fact I was a survivor.

After years of painful trauma treatment, the shame began to dissipate. I was finally able to respond to those who judged me by saying, “no, I couldn’t have made better choices or acted differently because I wasn’t capable of anything else at that time. In fact, my choices were successful because they worked: I survived.” I could also ask why others didn’t first think to question the choices my parents consistently made to abuse me in the first place (they were the adults, after all). I could answer that naïve question by asking, in turn, “who could I tell? Extended family members who suffered the same childhood trauma as my parents and who, as a result, aligned with them rather than their children? Or child services, who’d throw me into a game of misery-roulette, in which the chances that I’d end up in a better home would be about equal to the chances that I’d end up in a more toxic one?” We know all too well how often children are lost to “the system,” driven from one home to another until they are abandoned to the streets or to prison, destitute and alone (or worse), bereft of any home or future at all.

Today, I feel no shame, guilt, or regret for my past actions; in fact, I honor them as the clever and courageous ways I found to survive. I am not ashamed to say that I take pride in what I had to do in order to make it to where and who I am today, and perhaps my story may help others with similar stories find or build within themselves a pride where once there had only been the withering toxins of social stigma and self-contempt.

Shoplifting

By age 11, I was an expert shoplifter. I stole hygiene items and clothing, as my parents weren’t always able to provide me with my basic needs. My secrets included never carrying a bag, avoiding anything with a brand name, and using the privacy of dressing rooms, restrooms, and bulky product displays to hide items underneath my clothes. I never once got caught. White privilege and “benevolent” sexism served me well; the small blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl was never suspected of any wrongdoing. Shoplifting made it so that I always had soap, shampoo, deodorant, medication, underwear, school supplies, and school clothes. Later on, I was able to secure tampons, bras, and condoms.

As an adult, it took some time for me to refrain from shoplifting. I struggled financially for most of my young adulthood, but I was always able to procure my basic needs. I continued to shoplift for things that felt like necessities. It’s common for trauma survivors to continue to express behaviors that no longer serve them, to continue to perceive the world as irremediably unsafe, uncertain, and hostile. I retired from theft 14 years ago thanks to therapy and the realization that I’m able to provide for myself. Today, when I think of that little shoplifter, it’s not shame that I feel; but gratitude.

Hoarding

At age 9, my parents stopped preparing meals, and I didn’t have consistent access to food that I could prepare on my own. So, I collected dry food and hid it in cupboards, closets, and the attic. I would only eat from my stockpiles when I experienced hunger pangs, as these stockpiles helped me feel safe. I knew that I’d always have food no matter how bare the kitchen was, and this created a sense of security and empowerment.

As an adult, hoarding is a part of my life. I no longer stockpile food, but my medicine cabinet looks like I’m prepared for an apocalypse. The multiple bottles of over-the-counter pain relievers, antihistamines, decongestants, and supplements help me feel safe. As if I’m still that child with a severe headache who must find a way to cope with the pain on her own. Part of me is still afraid that someday I won’t be able to meet my basic needs and so I often find myself anxious to acquire and hold on to things in case I “need” them. My impulse to hoard is often calmed when I imagine that I’m telling my inner child that she hoarded in order to survive, and that it worked. I make sure to tell her that I’m appreciative for her hoarding and to remind her that she doesn’t need to do it anymore.

Parentification

By age 13, I perceived my parents as peers as opposed to caregivers. As a result of this change in my perception, I started to act as a parent. Parentification is a role reversal that is common in children who experience neglect. I cleaned the home, fielded calls from bill collectors, and provided emotional support to my mother. I was required to act as a parent for my younger brother who frequently had intense temper tantrums, which were later diagnosed as symptoms of bipolar disorder with manic episodes with psychotic features. I was often alone with him and required to hold him down when he attempted to harm me or himself. I received praise for my parental efforts and demeanor, which caused me to further internalize the role. Teachers, extended family members, and church leaders said I was “mature,” “so grown up,” and “a good kid.”

Of all of my behaviors, parentification has been the most difficult to escape. I became an adult who acted as a caretaker for everyone but herself. This role made it difficult for me to establish healthy adult relationships, since those who wished to take advantage of my caregiving tendencies were drawn to me, and I struggled to protect myself from them. I put my needs last (if I even considered them at all), as my self-worth was defined not by who I was, but only by what I could do for others. It took years of therapy, ending relationships which no longer served me, and a strong support system for me to be able to care for myself. Now, when I think of that parentified child, I grieve for my lost childhood.

Forgery

At age 10, I mastered the art of copying my parents’ signatures. Where I grew up, children were often left to figure out how to provide a parent’s signature for school-related matters when it was difficult or unrealistic for their parents to do so. When I discovered that my parents were incapable of signing documents in a timely manner and would become rageful when receiving inconvenient information, I stopped requesting their signatures. I signed my own report cards, field trip permission slips, and lunch money collection notices, and there was no need for my parents to ever see these documents. Luckily, I attended inner city schools that didn’t have the resources to track down parents or encourage them to engage in the lives of their children. Few teachers found it odd that they’d never seen or heard from my parents.

As an adult, I have no reason to commit forgery, as I no longer need my parents’ signatures. Unfortunately, as a young adult I lost scholarships and government grants that I needed for my education due to my parents’ lack of engagement and financial disclosure. Today, I can still sign my parents’ names perfectly, and when I think of that child forger, I smile with delight.

Detachment

By age 15, I’d become completely emotionally detached from my parents. When my father died suddenly, it wasn’t grief that I felt, but relief. The truth was something that is difficult for most to admit: I no longer loved my father, just as I no longer loved my mother. As a young child, I loved them both, and to lose this love was the most confusing and shameful experience of my life. I received messages from my family, community, and church that parents are entitled to the love of their children. This false assumption is often more detrimental to daughters who, as a consequence of patriarchal culture, are expected to act as caregivers for younger siblings and aging parents. To admit that I, a daughter, didn’t love my parents felt like a confession that I could not express to anyone. This detachment and shame would have a strong negative impact upon my ability to engage in healthy adult relationships.

As an adult, I developed a classic avoidant attachment style, for I struggled to trust and feel safe with people. I was 33 years old before I was able to experience secure attachment. The price was ending my abusive marriage, ceasing contact with my mother, adopting a loving cat, moving to a new city, welcoming healthy people into my life, admitting that I was not responsible for my detachment from my parents, and realizing that my parents were never entitled to my love.

There are many adults who still believe they were “bad kids,” who experience shame regarding what they did or didn’t do in order to survive childhood trauma. There continue to be families, communities, cultures, and religious organizations whose teachings may harbor good intentions, yet end up blaming victims and contributing to their shame. I hope that my story speaks to those who believe they were “bad kids” when they might have actually been, and still are, successful survivors.

Amanda Ann Gregory is a trauma psychotherapist, national speaker, and author who provides specialized speaking engagements for conferences, companies, and communities. Schedule a speaking engagement and follow on Instagram, Facebook, or YouTube.

All Rights Reserved | Amanda Ann Gregory, LCPC

Design & Consultation by Teresa Lauer, LMHC, GrowYourTherapyPractice.com *